A post by Maria Olczak and Andris Piebalgs (FSR Energy & Climate)

Over the last few months, satellite observations of methane emissions attracted a great deal of public and media attention. The satellite observations could revolutionise the way we track methane emissions. They hold a promise of frequent, low-cost measurements over vast areas, ensuring that no polluter, no matter where it is located, will be able to hide. In other words, satellites can make visible methane leaks, which are invisible to the human eye.

However, we should also be mindful of the limitations of remote sensing. They view only significant sources of emissions, the so-called super-emitters, due to the high detection threshold. Moreover, the reflective surface requirement essentially makes satellites blind to emissions over snowy, humid, cloudy and offshore areas. In addition to that, the regions located in high latitudes pose a significant challenge for satellite measurements.

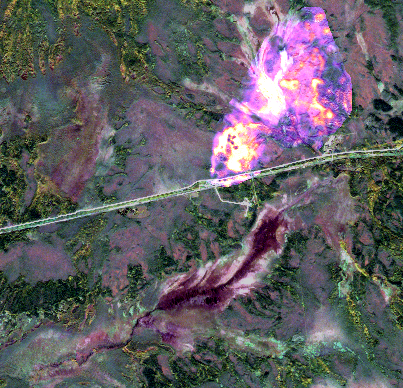

Yamal Pipeline, Russia, September 2019. Source: Kayrros.

However, the new generation of satellites, which will be launched into space in the coming 3-4 years, will overcome some of these limitations. And what is more interesting, there are more and more commercial projects in this respect. The Canadian company GHGSat launched two satellites (it is planning a constellation of 10 satellites); in effect, a detection threshold will drop from current 1000 kg/h to 70-250 kg/h. Whereas the satellites from Bluefield and MethaneSAT will be equipped with sun-glint geometry, allowing for observations over water. Those satellites will be launched in 2021 and 2022, respectively. The German-French mission MERLIN, planned for 2024, will be equipped with an active sensor allowing measurement of atmospheric methane at all latitudes all year long.

Although it is unlikely that one satellite or one company offering such services will be able to spot all emissions, a constellation of various satellites with different capabilities could make a difference. The question arises: how we make the best use of these data? Greater transparency is one thing, but to make sense of different satellite observations and effectively fix methane leaks on the ground within a short time, we need an organised process.

The International Methane Emissions Observatory (IMEO), comparing and reconciling bottom-up data reported annually by the companies through the OGMP2.0 with top-down – satellite, aerial – measurements, could step up the efforts to measure, report and verify methane emissions and to accelerate the reduction of methane emissions globally. It is essential, as the achievement of the 2030 climate objectives requires a significant and almost immediate reduction of emissions. The abatement of energy-related methane emissions is one of the easiest to achieve.

There is one more thing, maybe the most important. Namely, the political will to address methane emissions. So far, the governments largely overlooked the potential of methane emissions abatement, and only a few of them included a methane-specific objective in their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs). This may change as the Paris Agreement framework puts pressure on governments to step up their climate ambition every five years. As the International Energy Agency has recently demonstrated, there is already ample experience in various jurisdictions worldwide with different approaches adjusted to local conditions and the structure of the oil and gas operations in other parts of the world: regulatory (prescriptive and performance-based), economic and information-based.

Pipeline compressor station in Turkmenistan, November 2019. Source: Kayrros.

Some jurisdictions could and should lead global efforts to reduce methane emissions. We look at the US under the Biden Administration with the whole-of-the-government approach to climate change, the European Union unveiling its methane regulations by the end of this year, as well as Canada and Mexico – which already showed leadership in the reduction of methane emissions and the willingness to cooperate with other governments on this issue.

Also the pressure coming from large natural gas consumers and the investors, who see unabated methane emissions as a critical risk to the oil and gas industry’s role going forward in the clean energy transition, is an important factor.

Satellite technology can’t by itself reduce methane emissions, but provides good grounds for the actions all across the globe.

The views and opinions expressed in this post are solely those of the author(s) and do not reflect those of the editors of the blog of the project LIFE DICET.