A post by Robert Jeszke, Izabela Tobiasz and Maciej Pyrka (Centre for Climate and Energy Analyses – CAKE of the National Centre for Emission Management – KOBiZE).

The proposals for the introduction of a Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) for greenhouse gas emissions (GHG) have appeared for many years in the political debate of the European Union (EU). In 2019, the EU referred to a CBAM in the Communication from the European Commission (EC) The European Green Deal1 and, after that, consultations began in order to prepare the proposal to be included in the “Fit for 55” legislative package expected in June 2021. As part of the official consultation process, the Inception Impact Assessment and the Public Consultations took place in 2020. Following this process, the EC will finalize the Impact Assessment, which will accompany the proposal in June 2021.

Although the very idea of a CBAM is based on different concepts of solutions, its purposes are the same – to prevent carbon leakage in areas with lower ambitions in terms of GHG reductions or where equally rigorous environmental standards do not apply. There are a few options of CBAM mechanisms which are currently being considered by the EC: import tax, consumption charge, carbon added tax and system parallel to the EU ETS (preferred option), which involves the surrendering of allowances by the importer at the border.

One of the most sensitive issues causing the greatest controversy is whether a CBAM should fully or transitionally replace the current system of free allocation within the EU ETS. This issue is the most important for business, which invests in the perspective of 10-15 years and argues that the EU regulations and rules must give market stability. Meanwhile, changing the allocation rules during the period disturbs this view. The best example of that ongoing discussion is the resolution adopted during the European Parliament’s plenary at the beginning of the March 2021 which removes the reference to a CBAM as an alternative to current carbon leakage measures and avoids calling for the gradual phase-out of free allowances2.

The CBAM and free allowances mechanism existing in parallel was the subject of the analysis prepared by the Centre for Climate and Energy Analyses (CAKE) in September 2020. This CAKE Report3 generally analysed the impact of the introduction of the CBAM (import duty) on the economies of the EU Member States, among others, on price levels, changes in output, exports and imports, as well as emission levels using the global, multi-sectoral computable general equilibrium (CGE) model called CREAM (the Carbon Regulation Emission Assessment Model). The assumed climate policy envisages that the EU will enhance the GHG emission reduction target for 2030 from 40% to 55% of 1990 levels and subsequently introduce the CBAM.

It was assumed that the CBAM (import duty) should be levied on imports from sectors with high energy and carbon intensity in their output. The selected sectors have a significant share of about 48% of emissions in the EU ETS. They included4 :

- oil (manufacture of coke and refined petroleum products);

- ferrous metals (iron and steel production);

- non-ferrous metals (aluminium production);

- chemical products (manufacture of chemicals);

- paper products (manufacture of paper and printing); and

- non-metallic minerals (cement, lime and glass).

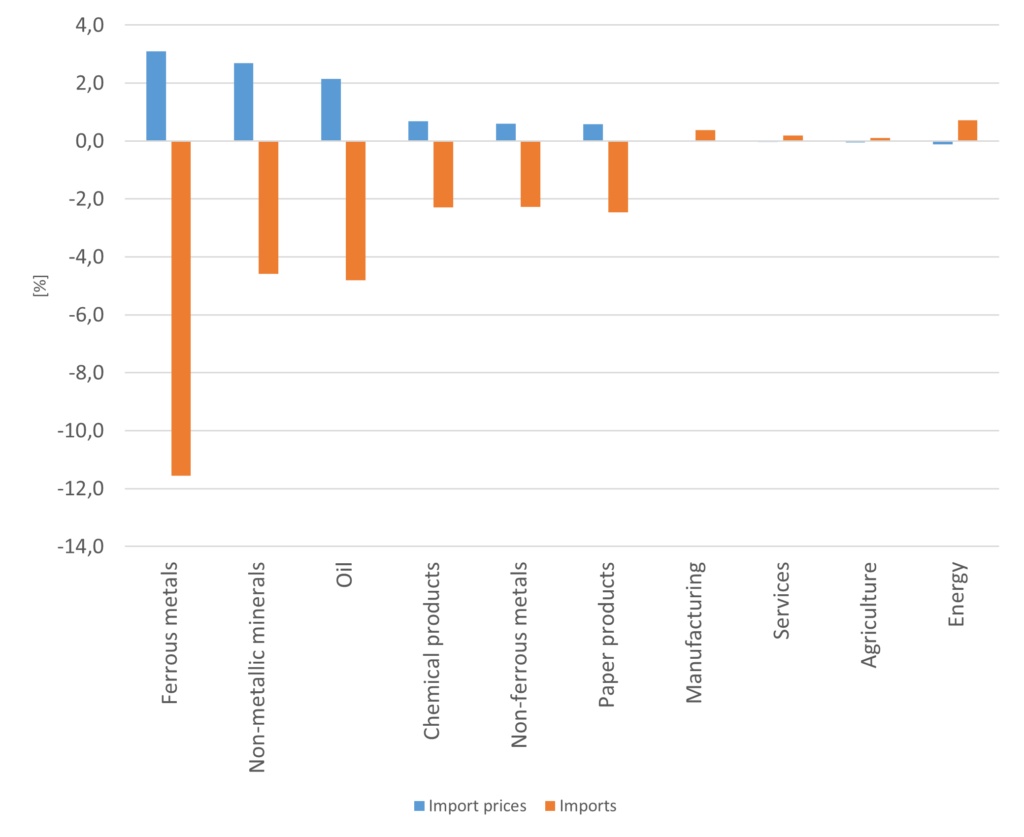

The implementation of the CBAM would cause an increase in the prices of goods imported from countries outside the EU, with a simultaneous decrease in the value of imports (see Fig.1). The greatest decreases in imports into the EU would come in the following sectors:

- ferrous metals by 11.6%;

- oil by 4.8%; and

- non-metallic minerals by 4.6%.

In contrast, the other sectors of the economy would see an increase in the value of imports (on average by about 0.3%), among others, as a result of substitution for the goods subject to the CBAM and slight deterioration of the competitiveness of goods manufactured in EU Member States (the implementation of the CBAM could cause higher production prices in the EU).

Fig.1. Prices and value of imports from outside the EU in EU-27.

In general, the introduction of the CBAM would cause an increase in the output in the sectors covered by that adjustment by 0.4%, primarily, as a result of substitution of imports by production in EU Member States. The greatest output increases would come in the sector of ferrous metals, by 1.6%, and the sector of non-metallic minerals, by 1.1%.

The introduction of the CBAM could also generate additional revenues for EU Member States. The largest revenues from the carbon border adjustment mechanism could be gained by Germany, i.e. USD 1.9 billion (EUR 1.36 billion5), while the lowest ones – Croatia, i.e. USD 0.04 billion (EUR 0.03 billion). The estimated proceeds from the carbon border adjustment mechanism in Poland could be USD 0.5 billion (EUR 0.36 billion), while the revenues from the CBAM in 2030 within the EU are estimated at about USD 10.6 billion (EUR 7.61 billion). The main factor affecting the value of revenues from the CBAM is the value of imports from outside the EU. In the discussion on the shape of the future EU climate policy, more and more often opinions can be heard that the possible proceeds from the CBAM could be earmarked as a contribution to the EU common budget.

The results of the analysis also show that the relocation of production and a change in the intensity of the trade between the EU and the other regions resulting from the implementation of the CBAM would contribute to a decrease in global GHG emissions by about 24 MtCO2eq. This change would be slight in relation to total EU emissions. Still, it would represent about 30% of the emission reduction level which would have to occur in the industrial sectors covered by the CBAM (and 10% in the EU ETS as a whole) if the EU reduction target is raised to 55% in 2030 relative to 1990 levels. It should be noted that, apart from the positive effects of the implementation of the CBAM, it also poses many risks, e.g. the fact that the CBAM is a measure to protect industry within the EU and in the longer-run will lead to less efficient use of resources (capital and labour). In addition, it should be considered that the analysis did not address in detail the legal and political issues related to the introduction of the CBAM that can pose the main obstacle to the implementation of this type of solution.

1 European Green Deal,

2 ERCST: “Status of the Border Carbon Adjustments’ international developments”; 15 March 2021

3 The effects of the implementation of the border tax adjustment in the context of more stringent EU climate policy until 2030, September 2020,

4 The sectors selected for the analysis include both activities directly exposed to a risk of carbon leakage and others that are part of the same sectors (NACE rev. 2) as the activities in the list of those exposed to a risk of carbon leakage.

5 The EUR/USD exchange rate = 1.392, according to Eurostat data (updated on 24.02.2020).

This blog post is based on the article:

- “Options and conditions for the introduction of the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) in the EU“, Maciej Pyrka, Izabela Tobiasz, Robert Jeszke, PhD Jakub Boratyński and Monika Sekuła, GO2’50: Climate. Society. Economy”, Issue No.01/2020

This article was prepared within the scope of the project: “The system of providing and exchanging information in order to strategically support implementation of the climate and energy policy (LIFE Climate CAKE PL)”- LIFE16 GIC/PL/000031 – LIFE Climate CAKE PL. The views and opinions expressed in this post are solely those of the author(s) and do not reflect those of the editors of the blog of the project LIFE DICET.