A post by Bernard Hoekman (EUI) & Fabio Santeramo (EUI and University of Foggia)

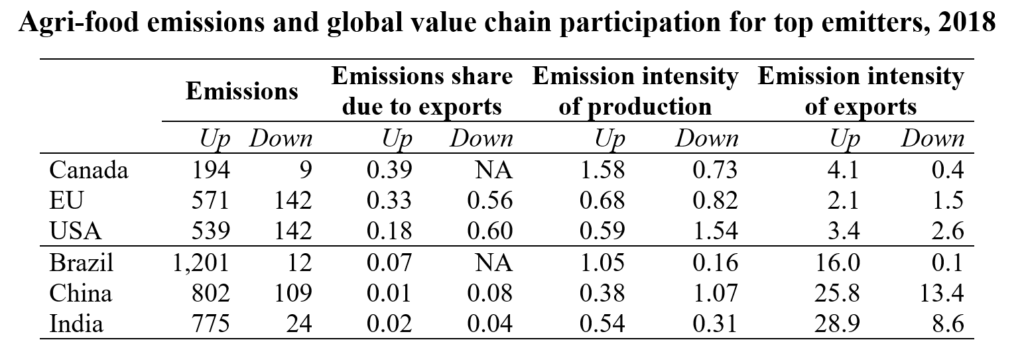

Agriculture is a top greenhouse gas emitting sector. Developed and developing countries contribute unevenly to global emissions from agricultural activities, with a ratio of about one to four[1]. The largest contributions are from upstream, trade-exposed, and less productive industries[2]. International trade in agri-food products contributes mostly through indirect emissions embodied in products. Developed countries tend to outsource pollution by importing dirtier inputs[2] and imposing trade policies that tend to be environmentally distortive[3]. Major agri-food economies differ significantly in terms of CO2 emissions due to exports and emission intensities (the ratio of CO2 equivalent emitted per tonne of output). As shown in the table below, Brazil, China and India have high emissions in upstream (input) industries, while Canada, the EU and the USA have higher emissions in downstream industries that are associated with trade activities.

These stylized facts illustrate both the need and the scope for international cooperation to overcome the political economy forces that have led to environmentally detrimental trade and agricultural support policies. Reforming domestic agricultural policies to target (shared) environmental objectives requires coordination among major agri-food producers and consumers that have very different specializations and emission profiles. The World Trade Organization establishes rules for trade and agricultural support policies as do some regional trade agreements. These rules affect a large share of global trade flows of agri-food products, facilitating trade and providing a framework for regulatory cooperation on matters such as product standards[4]. However, they do little to encourage lower GHG emissions through policies towards production or consumption of agri-food products. The focus is on reducing trade-distorting effects of policies, not on their climate impacts.

Multilateral agreements on agricultural policies are difficult to conclude. This was illustrated once again in the recent WTO ministerial conference, where consensus on a draft agreement on agricultural policy proved impossible. That draft agreement did not focus on the impact of agriculture on the climate, or how climate change will affect agriculture. An increasing awareness of the need to consider trade-climate change interactions, together with the importance of agriculture for food security and livelihoods may provide more fertile ground for deliberations among the largest global agri-food producers and consumers to identify reforms and actions to reduce global emissions associated with this strategic sector.

Open plurilateral agreements (OPAs) that encompass the major players are a potential instrument to guide reforms in agricultural support policies that move the sector toward zero-emissions. Differently from traditional trade agreements, OPAs can be domain-specific and provide a framework for a group of countries seeking to coordinate policies in a specific area[5]. Agriculture is currently a burden for the environment, with only a limited contribution to carbon sequestration through forests. The margins for improvement are large. A change in focus to ensure agriculture contributes to combatting climate change is overdue.

Notes: Up stands for upstream industries (i.e., farm-gate and land use change emissions, production and trade of raw agri-food products, domestic value-added agri-food products in the global value chain); Down stands for downstream industries (i.e., food processing and packaging emissions, production and trade of processed agri-food products, foreign value-added agri-food products in the global value chain). Emissions are in million tonnes of CO2 equivalent. Share of emissions due to exports are calculated by dividing total emissions of exports by total emissions. Emission intensities are measured as tonnes of pollution emitted (CO2 equivalent) per tonnes of output (production or exports).

References

[1] Mamun, A., Martin, W., & Tokgoz, S. (2021). Reforming agricultural support for improved environmental outcomes. Applied Economic Perspectives and Policy, 43(4), 1520-1549.

[2] Santeramo, F.G., Ferrari, E., Toreti, A. (2022) Achieving climate change and environment goals without protectionist measures: Mission (im)possible?. Presentation at the 2021 IATRC Annual Meeting.

[3] Shapiro, J. S. (2021). The environmental bias of trade policy. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 136(2), 831-886.

[4] Santeramo, F., & Lamonaca, E. (2022). Standards and regulatory cooperation in Regional Trade Agreements: What the effects on trade? Applied Economic Perspectives and Policy. https://doi.org/10.1002/aepp.13276.

[5] Hoekman, B., & Sabel, C. (2019). Open plurilateral agreements, international regulatory cooperation and the WTO. Global Policy, 10(3), 297-312.

The views and opinions expressed in this post are solely those of the author(s) and do not reflect those of the editors of the blog of the project LIFE DICET.